Policy Design – Form Follows Function

The Infinite Banking Concept is a process, not a product. Even still, the ideal vehicle for practicing Becoming Your Own Banker is a specific financial product. Like any product, form follows function. A whole life policy designed for IBC should be designed to fulfill its purpose and the needs of the owner. The function of the IBC policy is systematic accumulation of capital to provide for our need for finance. This defines the basic parameters for policy design. The specific needs of the owner will vary as each persons situation is different, and these determine the specifics.

This article is for those who are more interested in the particulars and details of IBC. Specifically, the details of policy design. I’m not going to get into weeds and minute detail, but I want to eliminate some of the noise and make clear my philosophy of policy design.

I also hope this helps other agents – NNI Practitioners – with their responses to client questions or critiques from other agents.

Before I begin, it is important to keep Nelson Nash’s rules in mind, specifically Don’t Be Afraid to Capitalize and Think Long Range.

When we speak of policy design, we are speaking of the ratio of Base to PUA premium paid, expressed as a fraction – like 10/90 or 40/60. There is no standard of whether Base is the first number and PUA the 2nd or vice versa. For the duration of this article, the first number will refer to the proportion of Base and the second number will refer to PUA.

Additionally, the Base percentage is the defining number, and it denotes how much of the total premium paid is Base. The PUA number is simply 100% minus the percentage of base. Many times, term riders are used in policy design, which I’ll explain further, but the cost of the term rider is not expressed in this format. Thus a “40/60” would be used to represent any policy that has 40% base – be it a policy with 5% term and 55% PUA or a policy with 1% term and 59% PUA.

The ratio also only refers to the first year. For a given client, maybe a policy with a $5,000 Base, and $12,500 max is recommended. This would be a 40/60 policy. Given the individual’s age and health rating we might include a 30-year term rider with a $500/year cost leaving $7,000 to PUA. This example would be a called 40/60 with 4% going to term. After 30 years, the term rider drops off and the premium is now $5000 to Base, which cannot change and a maximum underwritten PUA that is still $7,000 (assuming they maxed the PUA for all 30 years). In the 30th year, the policy is now 41.6/58.3. In discussing policy design, it is usually rounded, and this would still be called a 40/60 – this is just to demonstrate that the ratio changes throughout the life of the policy.

We must consider dividends. Hardly a word can be spoken about IBC without discussion of the dividends. What are dividends? They are rightly classified by the IRS as a return of premium. But they are also our share of company profitability, as policy holders of our mutually owned company. In practicing IBC our first choice for application of the dividend is to purchase more Paid-Up Additions.

Policies are underwritten with a limit to what the policy owner can purchase in PUA each year. However, there is no limit to PUA that can be purchased by directing your dividend to this end. In using the dividend to buy PUA, the insurer is paying more premium towards your policy – with no upper limit – on your behalf.

Total premium each year = Base + Term + PUA + Dividend

% Base = Base / Total Premium

Finally, we must understand the Modified Endowment Contract (MEC) and why we want to avoid our policies being designated as such. The IRS classifies a life insurance policy as a MEC when believes it is being used as an investment and not an insurance policy. This designation is determined by what is called the 7-pay test. This rule states that any policy will be come a MEC if the total premiums paid within a 7-year period exceed the premium paid for a 7 pay policy of the same death benefit.

We want to avoid MEC status because it loses many of the benefits. Policy loans are handled on a Last-In-First-Out basis, which means every loan is the coming from gains above and beyond premium payments and taxed as income at your top marginal rate.

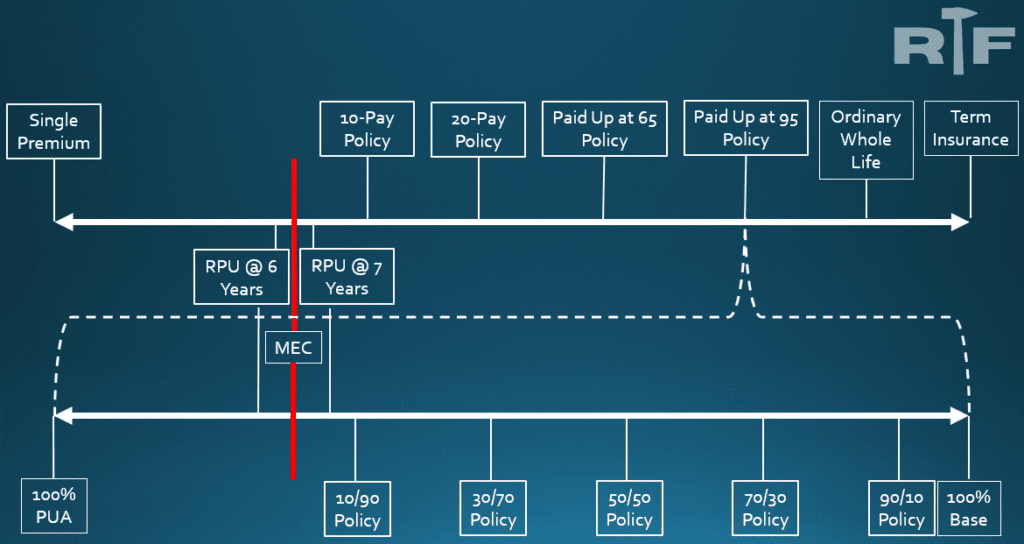

Ordinary Whole Life – 100% Base – can only become a Modified Endowment Contract (MEC) through owner action. Single Premium Whole Life insurance is automatically a MEC. Any policy placed into Reduced Paid Up (RPU) status before 7 years is also by definition a MEC.

Now also consider that a single premium whole life policy would be the same thing as a 100% PUA policy (if such a thing were possible). All of the purchased death benefit is 100% paid up at all times. With an ordinary whole life contract, no portion of the death benefit is fully paid for until age 65, 75, 95, or some other age as defined by the specific product.

Consider the charts below depicting the general relationship of different policy types and designs. The top is adapted from a chart in Nelson’s 10-hour seminar showing how the type of policy is related to MEC status. The bottom chart is demonstrating how policy design is related to MEC status. Each of 10-pay, 20-pay and Paid up at 95 can all be either 100% Base or have some percentage of premium to PUA. And any type of policy or design of policy can become a MEC through owner action.

Every illustration will say something to the effect of “this policy as illustrated [is or is not] a modified endowment contract.” Key words are “as illustrated.” An illustration is a snapshot in time that is inaccurate the moment it is printed. We do not know what dividend rates will be in the future – they can go up and down. We also do not know what we will do in the future – we may maximize the PUA one year and we may not in another year. And we may catch up missed PUA (if your company allows it). We may max out the PUA at policy anniversary or over time throughout the year. We may change the dividend election. All these things will cause a change in the dividend paid and death benefit vs what was on the original illustration. Bottom line, the future is unknown.

What is known is that if a policy violates the 7-pay test it is designated a MEC. Once it is designated a MEC it cannot ever become a non-MEC again. We also know that MEC determination is recalculated every time a substantive change to the policy is made. Buying PUA (dividend or out of pocket) is a substantive change. Term Policy dropping off is a substantive change. Renewing a “one year term” is a substantive change. What is also known is that dividends pull the policy left on the above chart – closer to the MEC line.

The volume of Base premium is fixed and grows at a fixed cumulative rate. If the PUA rider is maxed out, and dividends are paid, the volume of PUA grows at an increasing rate. The right side of the ratio grows faster than the left therefore the percentage decreases, moving policy left closer to the MEC line. See the below tables – the first for a 40/60 and the second for a 10/90 design.

If dividend rates increase, you will see the percent of premium paid to base be even smaller – the policy will be pulled left faster.

Let us return to the 7-pay test. There are two parts of the equation – death benefit and premium paid. Increasing dividends aren’t the only way a policy moves closer to the MEC line. If death benefit does not increase exactly “as illustrated” the policy will move left closer to the MEC line. Any reduction in PUA paid, whether from policy owner or from dividends, will reduce the death benefit purchased from what is illustrated.

In policy design our goal is to get close to that MEC line, but not so close that we inadvertently cross it. In Becoming Our Own Banker, we want to pay as much premium as possible for as long as possible.

Yes, if a policy is going to become a MEC, the company (or at least our preferred companies) will notify the policy holder and they will be given the option to have the premium returned or change the dividend election. But if this happens, your ability to capitalize has been limited and can only continue at the same level if you start a new policy and go through the start-up period again.

Sometimes those who take the above into consideration when designing policies for clients derided as “10/90 bashers” or “FUDs” (spreading Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt) and their position is twisted into a straw man of a claim that “10/90 can’t and doesn’t work.” No one says it can’t work. In fact, if everything goes exactly as illustrated it can and will work. Two key words: “if” and “exactly”.

As described above, dividends purchasing PUA pulls the policy closer to the MEC line. Dividends are not guaranteed, but our preferred company has paid dividends every year for 120 years. The younger the insured, the longer the policy will be in force, the more annual dividends will be paid – the farther left the policy will be pulled over time. The younger the insured, the more time is available for things to deviate from “as illustrated.”

The last part I’ll cover on policy design is the term rider. If necessary, a term rider may be included in an IBC policy for two reasons. The first is to increase the death benefit allowing us to purchase Paid-Up Additions without causing a MEC. It does this by increasing the gap between the cash value and the death benefit of the policy. The second, less important but still relevant, reason it is added is to create a small amount of drag on the policy so that cash value does not increase too quickly relative to death benefit. The term rider is a sunk cost, like any term policy. It counts towards the total premium paid for the 7-pay test but does not contribute to Cash Value. The amount of death benefit on the term rider is selected to find a sweet spot, allowing for the policy owner to pay as much premium as they want as long as they want.

Some agents advocate 10/90, or other skinny-base designs, because of higher cash value in early years. This focus on early cash value violates the two rules I reminded us of at the beginning. That higher early cash value comes at a cost: the higher risk of MEC status, that I just explained, and reduced dividends in the long run.

Each company and product is different, regarding how dividends are allocated. Generally speaking, dividends are paid at a higher rate of the base portion of the policy than the PUA. If you take two policies on the same individual, each with the same maximum premium – one 50/50 and one 100% base, the 100% base policy will have higher dividends paid. For those who have policies in place, look at your annual statements. For those who don’t, my first policy is a 40/60, the most recent annual statement shows that 22% of the dividend came from the 60% PUA and 78% of the dividend came from the 40% Base. This is because PUA premium is immediately liquid. It is available for you to take loans and does not contribute to generation of profit – divisible surplus.

Also, remember, dividends buy more death benefit and dividends are paid on dividends.

I understand. You just found IBC and you can see the value and you wish you’d started years ago. I was there too, and everyone who practices IBC went through this. And you must pay the start-up cost. You can pay now in the form of slightly reduced liquidity for a time, or you can pay later with reduced dividends and an increased chance of MEC status or reduced ability to capitalize. There are no shortcuts.

Consider if you have $100,000 that you want to move into a policy for banking. You have a policy designed to take $10,000 for 10 years. A 50/50 policy might have $5000 cash value available year 1 while a 10/90 might have $8k. You still have the other $90k available. A total of $95k liquid with a 50/50 or $98k with a 10/90. Do you really have plans for all $98k right now while still being able to pay next year’s premium? Do you really need access to that $3,000 now or are you just afraid to capitalize? Is the risk worth the 3% less in short-term liquidity?

There is no one-size-fits-all policy design. Everyone’s situation is different, and their policies will look different. In one sentence, my philosophy for policy design is this: To allow the policy owner to put as much capital into their policy for as long as possible.

Think long range. Don’t be afraid to capitalize.

If you’re ready to take control of the banking function, or just want to learn more, click to book a free call with an advisor today.

Semper Reformanda

All content on this site is intended for informational purposes only and is not meant to replace professional consultation. The opinions expressed are exclusively those of Reformed Finance LLC, unless otherwise noted. While the information presented is believed to come from reliable sources, Reformed Finance LLC makes no guarantees regarding the accuracy or completeness of information from third parties. It is essential to discuss any information or ideas with your Adviser, Financial Planner, Tax Consultant, Attorney, Investment Adviser, or other relevant professionals before taking any action.